Translating Nature Into Paint

from Colley Whisson

When approaching a painting, it’s important to make a clear distinction: the goal is not to copy nature, but to translate it artistically.

Many painters begin a work by thinking they must make an object look exactly like what it is — a car must look precisely like a car, a boat must look unmistakably like a boat, a figure must be anatomically correct. This way of thinking, however, can quickly lead us away from expressive painting and into tight, restrictive expectations.

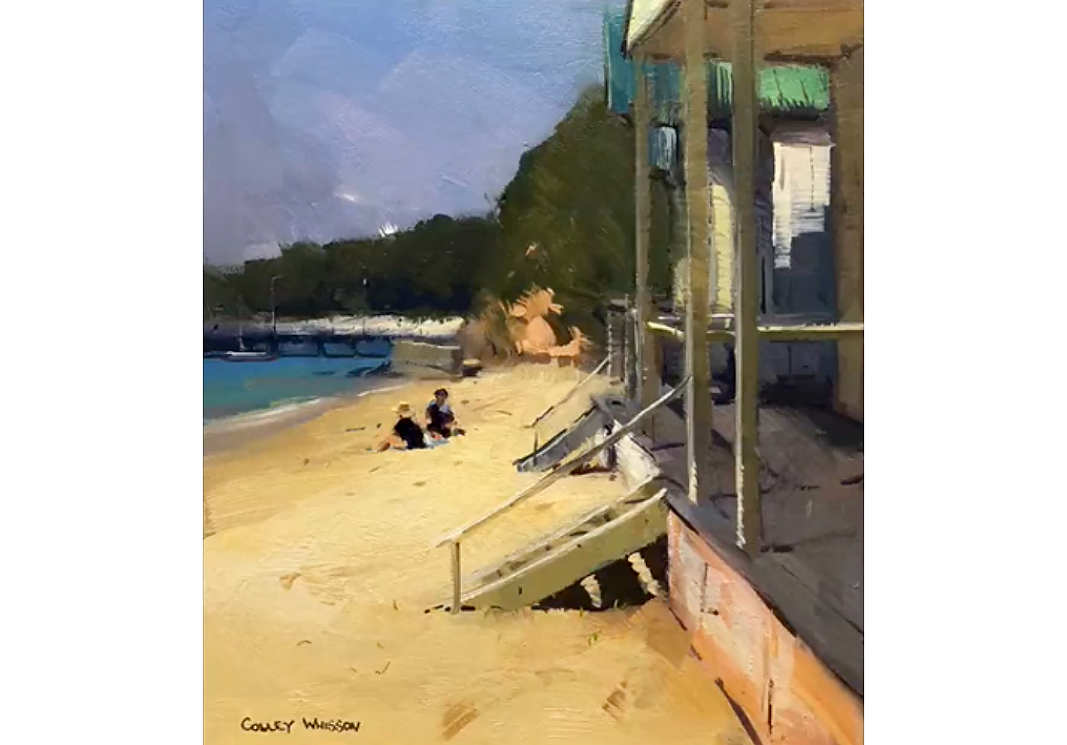

Instead, what we should be aiming for is a symbol of a shape — a visual suggestion that the viewer will read as a tree, a covered bridge, or a group of figures sitting on a beach.

Painting Shapes, Not Objects

At its core, a painted figure isn’t a real figure at all. It’s simply a shape, a value, and a color — a blob of paint placed deliberately on the canvas. When arranged convincingly, that shape becomes recognizable. The same is true for umbrellas, boats, trees, or buildings. They aren’t literal objects in the painting; they are suggestive renditions of observed shapes.

Once this idea truly sinks in, painting becomes far more liberating.

Design and Composition Come First

Strong painting begins with design and composition. Before worrying about detail, it’s essential to establish a clear underlying structure. For example, many successful landscapes rely on a classic S-shaped composition, guiding the viewer’s eye naturally through the painting.

Once composition is working, brushwork can begin to sing. At that point, the painter can focus on translating elements like a snow-capped mountain or a cast shadow — not through precision, but through confident, expressive marks.

A great example of this approach can be seen in the work of Arthur Streeton, one of history’s most celebrated landscape painters. His paintings remind us that clarity of design and suggestion often speak louder than detail.

Let the Viewer Complete the Story

If a shadow is convincing enough, or a touch of light on a tree trunk feels true, the viewer’s eye will instinctively fill in the missing information. This is one of the most powerful aspects of painting — allowing suggestion to do the work.

The moment we jump straight into trying to make something look exactly like a figure, we tend to tighten up. This tightening often stems from expectation — the expectation that every blade of grass, every line, every form must match the original object perfectly.

And that’s where we drift away from the heart of impressionistic expression.

Painting as Expression, Not Replication

Before the brush touches the canvas, it helps to visualize the mark you intend to make — whether it’s a shadow, reflected light, or a single expressive stroke. Think of each mark as an expression of an object, not an attempt to become the object itself.

This mindset frees the painter from the constraints of realism and opens the door to more confident, expressive work.

If a passage doesn’t look exactly like sand, that’s okay. What matters is whether the contrast of tones and the relationships between shapes are visually interesting and convincing.

Enjoy the Journey

Every painting is like a long drive. It might take two hours, six hours, or more. The key is to start in the right direction and travel at the right speed — not rushing, not tightening, but remaining engaged with the process.

When we focus on artistic translation rather than imitation, we don’t just reach the destination more successfully — we enjoy the journey itself. The brush marks, the decisions, and the act of painting become as rewarding as the finished work.

So push beyond merely copying nature. Translate it. Suggest it. Let the painting speak in its own visual language.

Study more with Colley Whisson below: